This summary was written by Rachel Levinson-Waldman, who served with OPC as a 2024 Ian Axford Fellow in Public Policy.

Read her in-depth report.

What is social media monitoring?

Social media monitoring in this context means just about any use of social media that isn’t for public education or outreach. It covers government agencies and public servants obtaining information about individuals or groups for law enforcement, intelligence, public safety, criminal investigations, regulatory enforcement, risk or threat assessment, or fraud detection.

What are the different ways that government agencies might access social media?

- Broadly, there are five categories. Most agencies don’t use every one of these, and some may use methods that vary somewhat.

Google or other general web searches that turn up publicly-available social media information – for instance, a public Facebook profile.

- Searches on social media sites for people, groups, hashtags, etc. Depending on the needs of the agency and the potential risk to employees, that could be through an account visibly affiliated with the agency or an alias (an account showing a different name and identity from the person operating it). Mostly this activity doesn’t involve interacting directly with other people on the platform, but in some situations could involve viewing or joining a group.

- Connecting directly with people on social media, via messaging, “likes”, etc. This typically involves the use of an alias account.

- Using third party tools for data collection and analysis.

- Taking over an account with the consent of the individual. This appears to be used mostly – perhaps solely – by Police and is carried out through specific forms that enable either temporary or permanent takeover. Note: the forms are included in the appendices of Rachel's report.

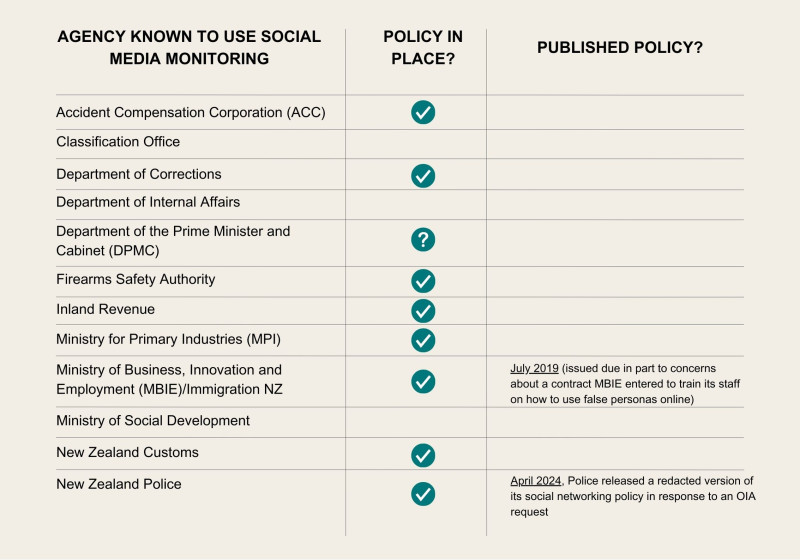

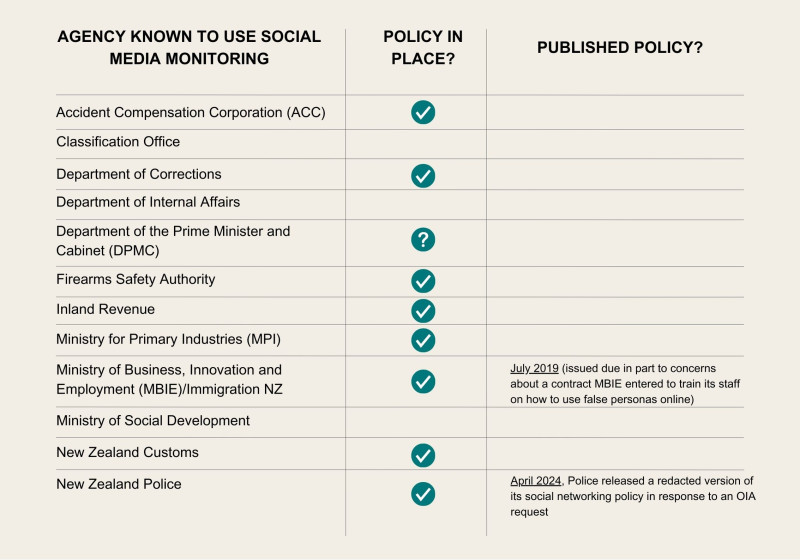

What agencies in Aotearoa New Zealand use social media and do they have policies in place?

Has the government said anything about developing and publishing policies on social media monitoring?

Yes. A 2017 joint report, by the Law Commission and Ministry of Justice, recommended that heads of enforcement agencies be required to issue policy statements addressing social media monitoring. In 2018, the Public Service Commission released model standards requiring agencies to establish a policy framework for information collection, which would also support the publication of policies addressing use of social media.

What does it matter if the government is looking at social media? Isn’t it just dog pictures and whatever people have chosen to put online?

Use of social media by government agencies to make decisions about investigations, prosecutions, risk monitoring, welfare benefits and other activities brings a variety of potential risks.

- Social media data can help create a surprisingly comprehensive picture of a person or group. Social media platforms host vast quantities of data from posts to likes to pictures, as well as a wealth of information about people’s friends, family, and other networks. Social media also makes it much cheaper and easier to assemble this information than older, analogue methods of information collection.

- Social media can be difficult to interpret. It’s highly dependent on cultural and language references, tone, in-group speak, and memes. Examples include British travellers who were barred from the United States after one tweeted out a joke that was misinterpreted and a high-ranking state official in the U.S. who lost his job after posting a picture from the rap group Public Enemy’s album that was interpreted as a threat to police. People also communicate in intentionally misleading ways on social media, as with white supremacist groups who use jokes to draw people in and try to obscure their intent.

- Social media monitoring can chill personal and political expression and other core democratic rights. As Dame Helen Winkelmann, now the chief justice of the New Zealand Supreme Court, has observed, privacy lies at the “heart of freedom of thought”. It is nearly impossible to dissent or to develop views outside the mainstream if you feel that you’re under surveillance. This risk is not merely hypothetical; there is a history both within New Zealand and around the world of state surveillance of activists and dissenters, and activists who identify as members of a marginalised group, including Māori and LGBTQ+, are at particular risk.

- There may be other impacts on marginalised or vulnerable groups. In addition to the targeting of activists, there’s a risk that governmental social media monitoring, even to detect threats, will be securitised. Muslim communities, for instance, have spoken out about the fact that security agencies were surveilling them prior to the Christchurch attacks rather than monitoring threats from white supremacists; LGBTQI+ groups have pushed back against coercive police activity; and Māori advocates have suggested (Tina Ngata, page 8) that the state is not equipped to provide protection through threat monitoring in light of its own history of harm to Māori. At same time, a significant amount of hate speech is directed against marginalised groups. This highlights the need for governmental agencies to act in close consultation with marginalised groups to determine what would most effectively support their safety, taking the groups’ lead as much as possible. Agencies should also pay close attention to the impact on tamariki and rangatahi, who are particularly vulnerable and are entitled to special protections under the Privacy Act.

- The increase of AI-driven tools supercharges many of these concerns, from facilitating lightning-fast data analysis that could create a holistic picture of an individual to being deployed in ways that – even inadvertently – are strongly biased against marginalised groups. These tools are typically developed using training data that is unlikely to adequately reflect the range of languages or cultural backgrounds in Aotearoa New Zealand. They often promise more than they can deliver. And it’s hard for AI to interpret nuance or context.

- Finally, the use of undercover social media accounts to engage directly with people poses special risks. A public servant could choose an online persona that has a different race, gender, or age from their real identity – something that would be impossible in person. They could even set up multiple personas, given enough time and technological capacity. This makes it particularly important that these practices are subject to stringent oversight and accountability measures. The 2017 joint report from the Law Commission and Ministry of Justice recommended that any agency undertaking covert operations – defined as an operation in which an enforcement officer develops a relationship with someone to obtain information – online or in person publish a policy statement and, in many circumstances, obtain a warrant.

Does New Zealand law prohibit social media monitoring?

No. The main relevant laws are the Bill of Rights Act 1990, the Search and Surveillance Act 2012, and the Privacy Act 2020. They all contain important safeguards but also leave critical gaps.

- The Bill of Rights Act 1990 provides important protections for democratic and human rights and prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, but it does not mention privacy and it can be overridden by other laws.

- The Search and Surveillance Act 2012 governs Police’s search and surveillance authority and, by extension, agents of other enforcement agencies. However, it does not address social media, and in their 2017 joint report, the Law Commission and Ministry of Justice concluded that it had “not kept pace with developments in technology”. The report recommended that the Act be amended to require heads of enforcement agencies to issue policy statements addressing social media monitoring.

- The Privacy Act 2020 requires that government agencies and private parties collecting personal information must have a lawful purpose for doing so and the collection must be necessary for that purpose. “Personal information” includes publicly available information, including on social media. But the Act has several carve-outs for publicly available information, and the 2017 joint report concluded that “we do not consider the principles in the Privacy Act provide sufficient protection against unjustified public surveillance”.

Do the major social media platforms have any relevant policies?

Yes. Facebook’s terms and conditions prohibit any user – including police officers and other law enforcement agents – from having an account under a false name. In addition, Facebook and Instagram (which are both owned by Meta), along with Twitter, all prohibit the use of their customer data for surveillance.

Other information

Back