Reviewed for relevance April 2025.

Since 2007, companies like 23andMe.com and Ancestry.com have made at-home DNA testing kits accessible to the masses. Through a simple online order, you can receive a kit, provide a saliva sample and return it to the company for analysis. Genetic data is highly sensitive given that, other than in the case of identical siblings, it is utterly unique to you.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing kits are billed as an inexpensive, non-invasive method of gaining personalised insights into your health, discovering distant family members and learning your genetic origins.

Some companies that sell DNA kits make dubious claims about what their tests can show and consumers who receive home DNA kits often sign onto opaque terms and conditions which allow their genetic information to be used in ways which would make most people deeply uncomfortable.

According to recent estimates, some 26 million people across the globe have used DTC DNA kits. The largest provider of this services, Ancestry.com, stated that by May of this year they had examined 15 million DNA samples. New Zealanders have a higher rate of testing than people in many other nations. A spokesperson for Ancestry.com told Stuff in 2018 that he believed testing was popular in New Zealand because many Kiwis wished to “find some connection to a bigger story, a bigger sense of belonging to the world.”

How do these tests work?

Although there are many types of at-home DNA tests available, the most common one helps consumers link up with distant relatives and discover their genetic roots.

Human DNA is 99.9% identical in all people. The remaining 0.1 percent contains what are termed single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). SNPs account for all variation between people including our height, build, hair type, eye colour and so forth.

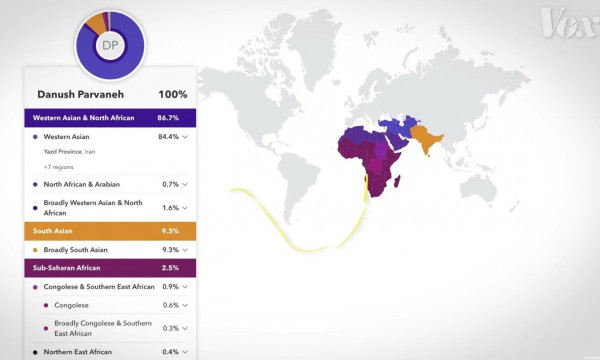

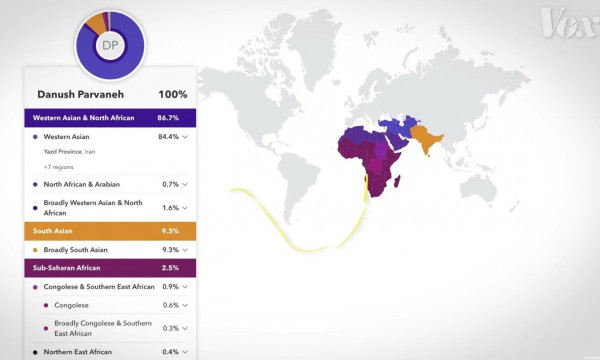

DTC DNA companies analyse samples collected from the public and compare the unique patterns of an individual’s SNPs to reference groups from around the globe. That comparison indicates how closely your pattern of SNPs resembles broad groups such as Western European, Northern African, East Asian and so forth. Once tests have been examined, consumers receive reports (such as the one below) which outline the percentage of their genes which seem to emerge from different countries.

Accuracy issues

Some experts have levelled criticism regarding the accuracy of take home DNA tests. Criticisms include that these companies generally don’t share their data, their methods are not externally validated and some consumers have submitted their DNA to multiple organisations and received back differing results. Such tests are perhaps best described as giving a probability of where your genes come from rather than a precise picture.

Many genetic markers may be found in multiple populations around the world. This means that trying to neatly categorise groups of people into groups like “European” or “West African” may gloss over massive intragroup variability. Experts argue that human genetic variation does not neatly fit into arbitrarily defined borders. Reporting from Vox highlighted that studies of DTC genetic testing showed that it may in fact “reinvigorate age-old beliefs in essential racial differences.” In other words, help to reinforce the idea that there are fundamental differences between people of different skin colours.

A report received from 23andMe by Vox journalist Danush Parvaneh outlining the broad categories of his genetic background. Source: Vox YouTube Channel

Opaque terms of services and sharing results with law enforcement

Dr Andelka Phillips is a senior Lecturer at the University of Waikato’s Faculty of Law and a Research Associate at the Centre for Health, Law and Emerging Technologies (HeLEX) at University of Oxford. She has focused her research on the regulation of the direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing industry. One of Dr Phillips’ main criticisms of the industry is the extremely long and complex terms of service that consumers must agree to as part of submitting their saliva samples.

Dr Phillips’ reviewed contracts for 71 of these companies which revealed some disconcerting clauses. Seventy-two percent of contracts included a clause allowing the company to alter terms (without the agreement of the consumer) with 28 contracts including a condition to alter terms at any time. Nearly half of reviewed contracts allowed for disclosure of personal data or genetic data to third parties in certain circumstances.

Twenty-five percent of contracts permitted disclosure of DNA data to law enforcement. In 2019, it was revealed that FamilyTreeDNA, a company which had collected more than 1 million DNA samples, had been working with the FBI to investigate violent crime.

Privacy considerations associated with these tests

For users of DTC DNA kits, there are major privacy questions including: How long do these companies keep consumer’s genetic information? Who is the data shared with and for what purposes? And are you able to request for your information to be deleted from the company’s records?

Some companies in this industry have been explicit in stating their real motives for collecting people’s DNA. 23andMe, at their launch in 2007 told the San Francisco Chronicle: ““Once you have the [genetic] data, [the company] does actually become the Google of personalized health care.” Understanding variations in the human genome may assist with drug development and give DTC DNA companies valuable insights into the global pharmaceutical industry worth $1.2 trillion USD in 2018. Drug-company giant, GlaxoSmithKline invested $300 million in 23andMe in 2018 with an eye to using the DNA company’s de-identified, aggregate customer data for drug research. As this Atlantic article noted, “you don’t make that kind of money selling $99 spit kits.”

Dubious tests conducted by some DTC DNA companies

The lack of regulation in the DTC DNA industry is apparent in the fact that some genetic testing companies offer to reveal information about people that there no scientific evidence they can deliver. Examples include tests that claim they can show whether your child has “language learning” genes, will possess innate football talent or even whether they are a “picky eater”. The evidence that DNA can reveal any of these traits is doubtful at best and more likely, completely misleading.

One savvy Canadian man decided to assess the accuracy of a Toronto-based DTC DNA lab which charged $250 dollars to conduct a check into your ancestry. He submitted three samples, two from himself and one from his girlfriend’s dog for analysis. The results he received showed that both he and Snoopy the chihuahua shared identical “indigenous” ancestry. It emerged that the tests were being used by some wealthy Canadians to fraudulently attain indigenous status and save money on some taxes.

health,

data,

DNA,

23andme,

Ancestry.com

Back