Our website uses cookies so we can analyse our site usage and give you the best experience. Click "Accept" if you’re happy with this, or click "More" for information about cookies on our site, how to opt out, and how to disable cookies altogether.

We respect your Do Not Track preference.

When Ross Compton’s house caught fire in September 2016, he was able to escape unscathed, with a suitcase full of clothes and the charger for his external heart pump. But when the 59-year-old US man explained to arson investigators how he’d broken the window with his cane and hurled his most important belongings out the window before scrambling to safety, they weren’t convinced. And so, in a twist that would have been science fictional a few years ago, they interrogated his heart.

To put that more prosaically, local police obtained a search warrant for all the electronic data stored in Mr Compton’s pacemaker. They decided that the information held in this device suggested Mr Compton had not actually grabbed his possessions and scarpered as his house burned as he claimed. As a partial result of the pacemaker data, he was charged with aggravated arson and insurance fraud.

Mr Compton’s case may not spark much sympathy, since he was discovered in the (potential) commission of a crime, and in one sense the use of his pacemaker data as evidence of his alleged actions is no different from a photo of a footprint. But it raises some big questions. Are we ready to implant devices in our bodies even if they might betray us?

Fitness trackers and health apps on cell phones are becoming ubiquitous and socially accepted as ways to let us manage our own health, even though we are almost certainly unaware of the breadth and depth of the information these devices collect about us. But at least those we can choose to leave at home. Someone with a pacemaker, or surgically-installed diabetes monitor, or any of the hundreds of ‘smart’ prosthetics, monitors and therapeutic devices that are being developed right now, may have no such choice.

Medicine is a tightly regulated field, but regulations in this area are mostly made under the Medicines Act and focus on certifying the physical safety of medical devices. Because there is no law specifically regulating what happens to information coming out of an implanted device, in New Zealand at least, the general privacy rules in the Health Information Privacy Code (HIPC) apply.

Privacy is about control of personal information in the face of the technologies that lessen that control. The HIPC helps support that control by regulating how health information is collected, held, used and disclosed. It requires agencies collecting information to be clear about their purpose for doing it, and to clearly communicate that purpose to the people concerned. Transparency is important when signing up for a supermarket rewards card, but it’s crucial when we’re having something put inside us that can talk to the world. Transparency in information collection gives us the background we need to make decisions about who gets to see our information.

So what do you need to tell your patients when you think some kind of implanted device might be in their future? You’re probably not the one collecting the information, so there isn’t likely to be any legal obligation on you. But it’s sensible to keep abreast of developments.

Start with what it means to call a device ‘smart’. Smart can mean a device that does innovative things with information to make new ways of living possible. Smart is also often a cool-sounding buzzword for anything that has some kind of computer and a wireless connection, no matter how absurd. There’s a website that collects examples of things like Wi-Fi wine bottles and app-enabled mattresses that is an illuminating read.

For a smart device to be worth its silicon, it needs to produce more value than the potential trouble it causes. The trouble with putting a computer and a Wi-Fi connection into anything is twofold - first, computers have software and software gets bugs. Either you keep up with software updates or you open your device up to online attack. Having to patch your kettle before it will boil for you is not a good use of anyone’s time.

But if you ignore software updates, or the manufacturer doesn’t bother to provide them, the second problem can arise. Anything that’s left online and unpatched is vulnerable to attack and compromise, sometimes within minutes. Malicious ‘DDOS’ (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks often use vast ‘botnets’ of compromised household devices to shut down websites.

Is it too cynical to assume that similar problems could apply to the high-end world of implantable medical technology?

There’s also the major issue, as discovered by Mr Compton, of what happens to all the data that gets collected by smart gadgets. It has to be collected for a purpose, and stored, and used, and disclosed. What’s the purpose? Where is it stored? How is it used? To whom is it disclosed? These are all questions you should ask about every smart device, and when it comes to technology that your patients might trust their lives to, you should ask it until you get a satisfactory answer.

GPs have always been on the frontline when it comes to conveying how technology can affect their patients in areas like medication and surgical procedures. It’s a short leap to have just as clear an idea of the informational risks and benefits of new technology.

This article was first published in NZ Doctor on 29 March 2017.

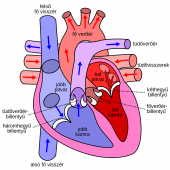

Image credit: Human heart illustration via Wikipedia - Creative Commons

Back